Interview with Gary Chang : ‘The point is to squeeze the space and squeeze the time’

Domestic Transformer, Hong Kong, 2007. © Gary Chang

Curator and critic Vladimir Belogolovsky recently spoke with Hong Kong-based architect Gary Chang about his background, his firm, EDGE Design Institute, and some of the projects he has created since the completion of the famous Suitcase House at the Commune by the Great Wall two decades ago.

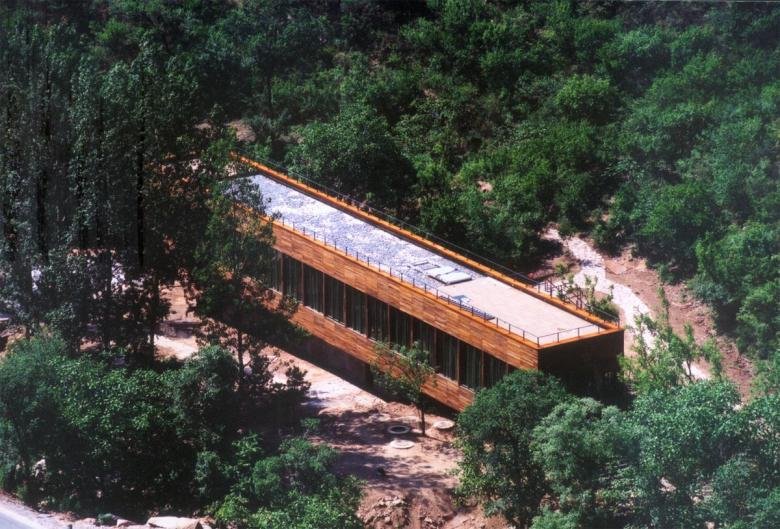

Hong Kong-based architect Gary Chang became internationally known when his first ground-up work— the Suitcase House — was completed in 2002 at the Commune by the Great Wall near Beijing. That compound’s original villas, designed by some of the most innovative architects from Asia, both established and up-and-coming, were widely publicized both in popular and professional media. The project was awarded a special prize at the 8th Venice Architecture Biennale, in 2002. The Suitcase House served Chang as a manifesto of sorts to put his ideas — transforming tight spaces into different rooms, in this case, through the use of sliding walls and opening floor panels — into practice. Since then, all Chang’s projects deal with spatial transformations and maximizing the use of compact spaces, abilities he has nurtured since childhood.

The architect was born in 1962 in Hong Kong, where he grew up in a tiny 340-square-foot (31.5m2) apartment that he shared with his parents, three younger sisters, and another unrelated person, a subletter. Chang lived there throughout the years he was a student at the University of Hong Kong. It was only a year after he graduated, in 1987, when his family could finally afford a bigger place and moved out. Taking advantage of the then-recently introduced low-interest down payment loans, he purchased his family’s old rental apartment.

Suitcase House, Commune by the Great Wall, 2002. © Gary Chang

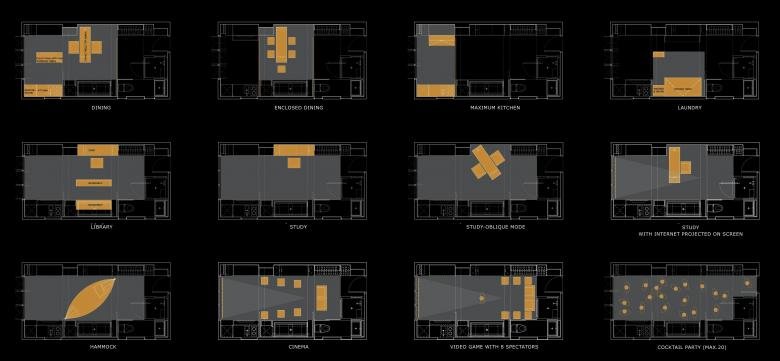

He started his own practice, EDGE, with a partner in 1994 and went solo four years later, renaming it the EDGE Design Institute. He still resides in the apartment he grew up in; it serves as a laboratory to test innovative ideas. In 2007, for example, all partitions were replaced with wall elements that move, slide, and swing to transform various areas of the puzzle-like apartment into what the architect calls Domestic Transformer: 24 different “rooms,” or functions, including a library, guest bedroom, walk-in-closet, home spa, dining, home office, cinema, and cocktail lounge for 20 guests.

Apart from the Suitcase House and Domestic Transformer, the architect has designed the MoMA Design Store in Hong Kong; hotels and apartment buildings across Asia; boutiques, office and apartment conversions; interiors for a private jet and yacht; furniture, light fixtures, design products for Alessi and Hennessy; and sportswear. During a recent visit to Hong Kong I visited Chang’s small but busy duplex office, which is also a spatial transformer in its own right. We sat down for a conversation about the architect’s apprenticeship experience before starting his own practice, his first breakthrough, his desire to occupy the whole space at once, wanting to replace all building types with a single hybrid type, and his hobby of staying at unusual hotels (his current list exceeds 1,500 hotels, at least 50 of them in Hong Kong).

MoMA Design Store, K11 Musea, 2019. © Gary Chang

Vladimir Belogolovsky: What was your time like between your graduation from the University of Hong Kong and starting your own firm?

Gary Chang: I worked at the Hong Kong office of Palmer and Turner, one of the oldest architectural practices in the world, for seven years, starting immediately after my graduation and until I started my own firm in 1994. My professor arranged this job. So, I never applied for a job, never had a job interview, and I have never written any application letters in my life. [Laughs.] At the time, there was only one school of architecture in Hong Kong and there were just 30 graduates every year. So, we were all in high demand.

What kind of projects did you work on at Palmer and Turner?

I was part of a small design team at the firm, working directly under one of the directors, Remo Riva, a Swiss architect. I was quite spoiled there. Other designers worked on many projects simultaneously. But I was working on just one project at a time and just several during those seven years that I was there — all very important for the company. The first one was the Bank of China in Macau. Then there was the Entertainment Building on Queens Road in Central, Hong Kong with strong postmodernist features. I worked on that from beginning to end; it was completed in 1993. Then I worked on the design of a large shopping mall in Causeway Bay in Hong Kong. It was a very complex project with a cineplex component.

What led to starting your own practice, EDGE?

Parallel to working on all those projects at Palmer and Turner, I started helping my uncle with two small buildings for his company here in Hong Kong: one for an advertising firm and one for a movie equipment rental company. I also started entering and winning competitions. But I never became a licensed architect; I never passed the exam. One of my best friends is a registered architect; she signs my drawings. So, there are ways around these things. [Laughs.] Because I was not registered, I was not promoted at the firm. So, after seven years I left — quite dramatically, I should say. I wrote a resignation letter, a seven-page written protest with a very detailed explanation of why I was quitting. I even drew a chart of my salary history, which was growing slowly and, at some point, it even dropped! This was an open letter that I left on everyone’s desk and left through a fire escape exit, so no one would see me. [Laughs.] I never went back.

Then I started my own company, EDGE, with a partner, Michael Chan. Initially, we worked at my uncle’s space. And we relied on his resources and even his secretary. [Laughs.] We split up in 1998; I renamed my firm EDGE Design Institute to emphasize my research-based approach, while his firm became EDGE Architects. The name EDGE reflects my rebellious character and refusal to define anything; I want to be on the edge or on the borderline.

Suitcase House, Commune by the Great Wall, 2002. © Gary Chang

Would you say that your Suitcase House at the Commune by the Great Wall, completed in 2002, was a precursor for your Domestic Transformer, a conversion of your own apartment in 2007?

I would say so. That was the beginning of playing with transformation ideas, a manifesto of sorts, which led to many other projects since then. The same year I did Kung Fu Tea Set Tea and Coffee Tower for Alessi. It is also a transformer; it never looks the same, and all pieces can be stacked into a single tower. For sure, the Suitcase House is the most important project for our studio. It was the first house I ever designed and we had total freedom, only limited by the size of 250 square meters and the need to use local materials and labor.

was the main idea?

The idea for the open house that transforms came instantly, in the very first discussion. The first sketch shows everything. The project was curated by Yung Ho Chang. He invited all the architects, a total of 12 to design 11 villas and a clubhouse. Other invited architects included Shigeru Ban, Kengo Kuma, Cui Kai, and Seung H-Sang.

Suitcase House, Commune by the Great Wall, 2002. © Gary Chang

When you describe your work, you use such words as movable, transformable, modular, and efficient, and such phrases as continuous landscape, maximizing space, domestic transformer, nothing is permanent, and an ongoing experiment. How else would you describe your architecture?

It is about the smart use of resources, including time, of course. I am always in search of new urban dynamics. And to me, architecture is not only about emotions but also about science and precision.

You said, “I don’t move from one room to the next; instead, home moves for me.” Could you elaborate?

I always want to occupy the whole space at once, especially if it is tight. And I want the walls to move for me to reveal different functions. And when these walls move, I am in control of how big different rooms can be. And if I invite friends, the whole thing can transform. It was the experience of growing up in Hong Kong that made me think this way and be mindful of limited space and resources. Transformability is always on my mind. The point is to squeeze the space and squeeze the time. And I always think of my neighborhood and even the entire city as the extension of my home, any home. In that way, your space is never too small. So, I am content and would not want to move to a bigger space. Instead of buying a bigger apartment I would rather spend more time in the city and fly to other places to experience them more frequently.

Domestic Transformer, Hong Kong, 2007. © Gary Chang

Speaking of flying to different places, you have a hobby of staying at unusual hotels. What are you learning from that experience?

I am collecting different experiences of staying at many different hotels. I stayed at more than 1,500 hotels, including at least 50 right here in Hong Kong. Apart from the experience, which I love, I explore how to redefine the boundaries between home, hotel, and apartment. I believe these types should all be one hybrid type. Each can be learned from to enrich the overall experience. So many typologies of various buildings are almost identical. It is depressing. There should be no fixed layouts for any type.

Is there one particular building built in Hong Kong in recent years that you feel most excited about?

Instead of a building I would name a piece of infrastructure: the Central–Mid-Levels escalator and walkway system finished in the early 1990s. On the one hand, it is quite ugly, but I think the impact on the city is paramount. It transformed people’s lives in that part of the city. Initially, the idea was to relieve the pressure of vehicular traffic. But it sparked so many activities there; it was turned into the SoHo of Hong Kong, a major tourist destination with vibrant street life, populated with restaurants, bars, nightclubs, shops, and galleries. The place is booming. I also like the fact that it is on a slope. You feel a strong presence of the earth under your feet there.

And the second most important part of the city is the waterfront. It is an ongoing project that has become quite extensive. These places attract joggers and whole families to camp. Finally, Hong Kong is a city where people can enjoy themselves.

Gary Chang